Blog

Beauty Shoulder: Graceful Curves & Soft Aesthetics

Jingzhou vs Duo Zhi: Dialogue of Master Forms

Two Lineages, One Craft—How Shape, Proportion, and Intent Define Yixing Excellence

Within the world of Yixing teaware, few comparisons are as revealing as Jingzhou versus Duo Zhi. These are not just two teapot shapes; they are two master lineages—two ways of thinking about proportion, posture, and brewing logic. Collectors and tea practitioners often describe them as distinct “voices” on the tea table: Jingzhou, measured and composed; Duo Zhi, expressive and forward. To understand their differences is to understand how form becomes philosophy, and how a teapot can quietly guide the way tea is brewed, served, and experienced.

Jingzhou and Duo Zhi both arise from the same Yixing soil and craft tradition, yet they embody different priorities. One leans toward literati restraint, the other toward dynamic articulation. Neither is inherently superior; each is a refined answer to a different set of questions: How should tea move? How should heat be held? How should the brewer’s hand meet the clay? This is why their comparison is so enduring—it is less a contest and more an ongoing dialogue within the art of tea.

I. Lineage and Identity

Where Each Form Comes From—and What It Was Made to Express

Jingzhou is often associated with a lineage of calm, upright forms that echo the temperament of the scholar’s studio. Its stance is balanced, its shoulder line clean, its proportions measured. The body tends to be steady and composed, with a geometry that favors stability and clarity. Historically, such forms appealed to literati who valued objects that reflected inner order and disciplined thought. A Jingzhou teapot on the table feels like a quiet, confident presence—never loud, but unmistakably grounded.

Duo Zhi, by contrast, carries a more dynamic identity. Its posture often leans slightly forward, its transitions between body, spout, and handle more pronounced. The form feels ready to move, as if the teapot itself is participating actively in the brewing process. This lineage reflects a different emphasis within Yixing craft: one that celebrates articulation, flow, and the expressive potential of clay. Where Jingzhou suggests stillness, Duo Zhi suggests motion.

Both forms were refined over time by master potters who balanced aesthetics with function. Jingzhou’s identity is shaped by proportion and restraint; it is a form that communicates confidence without spectacle. Duo Zhi’s identity is shaped by articulation and flow; it is a form that communicates energy without chaos. Culturally, they mirror two complementary ideals in Chinese aesthetics: the scholar’s calm and the artisan’s vigor. Together, they show how a single material—Yixing clay—can carry multiple, equally valid interpretations of beauty and purpose.

II. Structure, Proportion, and Functional Logic

How Geometry Shapes Heat, Flow, and Leaf Expansion

Jingzhou’s geometry favors a low center of gravity and a stable base. Its body proportions allow tea leaves to expand evenly, making it well-suited for oolong, aged teas, and pu’er that benefit from consistent heat retention. The shoulder line is clean and unembellished, supporting a lid fit that minimizes heat loss while allowing quick adjustments. The spout is engineered for a smooth, controlled pour—ideal for sessions where clarity and repeatability matter. The handle arc is comfortable and measured, encouraging a steady hand and a deliberate pace.

Duo Zhi’s structure emphasizes dynamic flow. Its body often features more articulated transitions, creating internal spaces that can gently agitate leaves during pouring—useful for teas that respond well to active infusion, such as certain dancong or high-aroma oolongs. The spout angle tends to be more assertive, enabling a faster, more decisive stream. The handle is shaped to support quick movements without sacrificing grip, making it suitable for brewers who prefer a lively tempo. The lid fit balances heat retention with responsiveness, allowing the brewer to modulate temperature with subtle lid adjustments.

Clay choice further refines performance in both forms. Zisha variants often enhance body and depth, making them ideal for darker teas and aged leaves. Zhuni can emphasize aroma and brightness, pairing well with fragrant oolongs or lighter teas. Over time, authentic Yixing clay in either form develops patina, improving responsiveness and producing more nuanced infusions. The teapot gradually “learns” the brewer’s habits, becoming a more precise tool the longer it is used.

III. Presence on the Tea Table

Atmosphere, Rhythm, and the Way Each Form Organizes Space

On the tea table, Jingzhou acts as an anchor. Its upright posture and balanced proportions create a visual center that calms the surrounding arrangement. It pairs naturally with minimalist setups, celadon cups, and clean-lined trays. The teapot’s presence encourages slower movements and attentive brewing, making it a favorite for sessions focused on clarity, contemplation, and quiet conversation. Its geometry draws the eye without dominating the scene, allowing the tea itself to remain the main focus.

Duo Zhi brings a sense of momentum. Its forward-leaning silhouette and expressive spout dynamics invite a more active style of pouring. It pairs well with textured materials—bamboo trays, rustic stoneware cups, and tea pets that add personality to the table. The teapot’s presence encourages a lively rhythm, making it ideal for social sessions or teas that benefit from energetic handling. It organizes space through movement rather than stillness, creating a tea atmosphere that feels engaged and responsive.

Both forms can harmonize with a wide range of aesthetics, but they shape the mood differently. Jingzhou supports a meditative tone; Duo Zhi supports a conversational tone. Choosing between them is not only a technical decision—it is an atmospheric one. The form you place at the center of your tea table will quietly influence how the session unfolds.

IV. Choosing by Tea, Style, and Intention

Which Form Fits Your Leaves—and Your Way of Brewing

For teas that reward consistency—aged oolong, sheng or shou pu’er with layered infusions, and darker teas that benefit from steady heat—Jingzhou is often the preferred choice. Its controlled pour and stable body help maintain a reliable brewing environment, allowing flavors to unfold gradually and cleanly. It suits brewers who enjoy measured movements, careful timing, and a focus on repeatable results.

For teas that thrive on agitation and expressive pouring—fragrant dancong, certain high-aroma oolongs, or teas that respond well to quick, decisive infusions—Duo Zhi can bring out brightness and lift without sacrificing structure. Its dynamic geometry and assertive spout make it a natural partner for brewers who like to adjust on the fly, responding to the tea in real time.

Many practitioners keep both forms in rotation, choosing based on tea type, mood, and the desired atmosphere of the session. In practice, the best way to decide is to brew with intention. Pay attention to how each form affects leaf expansion, pour clarity, and temperature stability. Notice how the teapot changes the pace of your session and the feeling of your tea table. Over time, Jingzhou and Duo Zhi reveal themselves not as rivals, but as complementary tools that expand your range as a brewer.

Closing Reflections

Two Voices, One Tradition—A Dialogue That Deepens the Art of Tea

Jingzhou and Duo Zhi represent two masterful answers to the same question: how should a teapot embody both beauty and function? One speaks in the language of proportion and calm; the other speaks in the language of movement and clarity. Both are rooted in Yixing craft, shaped by cultural memory, and refined through daily use. Choosing between them is less about allegiance and more about understanding your tea, your rhythm, and the atmosphere you want to create.

In the end, the dialogue between Jingzhou and Duo Zhi enriches the tea table. It invites us to see form as philosophy, performance as practice, and clay as a living partner in the art of brewing. That is the enduring gift of Yixing: a tradition where shape carries meaning, and meaning is felt in the hand.

Curated Pieces, Crafted Purpose

Explore the selections below—where craftsmanship meets desire, and your tea table finds its fire.

「井栏花鸟 · Well Fence Harmony」 — 130ml Boutique Handmade Yixing Purple Clay Teapot | Well Fence Form with Flowers & Birds Engraving · Raw Ore Red Downhill Mud · Zisha Gongfu Gift Edition

「井栏龙韵 · Well Fence Harmony」 — 240ml Handmade Yixing Purple Clay Teapot | Well Fence Form · Raw Ore Red Leather Dragon Mud · Zisha Gongfu Tea Set

「侘寂壶 · Kurohō」 — 145ml Handmade Coarse Pottery Teapot (Retro Japanese Style · Rustic Clay Body · Gongfu Infuser Pot)

「供春壶 · Tribute to the Roots」 — 140ml Handmade Yixing Purple Clay Teapot (Gong Chun Style · Raw Ore Zisha · Mesh Filter · Folk Artisan Work)

「六方石瓢 · HexaScoop」 — 200ml Handmade Yixing Purple Clay Teapot | Hexagonal Stone Scoop Form · Raw Ore Zisha · Vintage Gongfu Teaware Gift Edition

「创意梨壶 · Hearthdrop」 — 200ml Handmade Yixing Purple Clay Teapot (Raw Ore Zisha · Pear-Shaped Form · Famous Artist Work)

「刻韵壶 · Carved Harmony」 — 210ml Handmade Yixing Teapot (Raw Ore Zhu Ni Clay · Traditional Carved Form · Built-in Strainer)

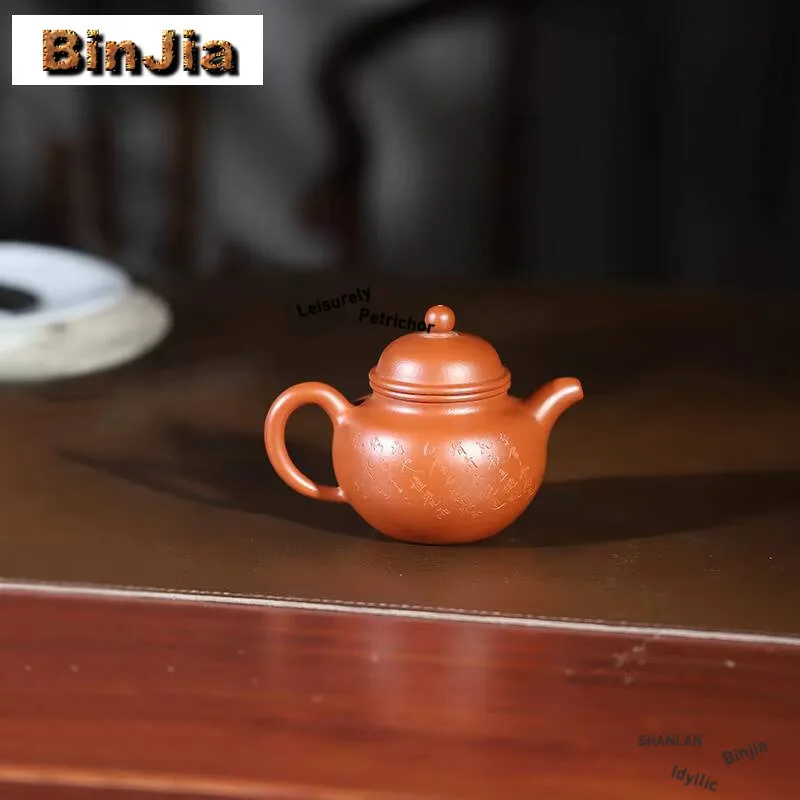

「名家梨壶 · Masterseed」 — 85ml Handmade Yixing Purple Clay Teapot (Raw Ore Zisha · Pear-Shaped Form · Famous Artist Work)

「呼吸壶 · Breathing Vessel」 — 160ml Master-Crafted Yixing Teapot (Zhu Ni Clay · Dual-Pore Structure · Ming Dynasty Heritage)

「和饮壶 · Harmony」 — 300ml Master Handmade Yixing Purple Clay Teapot (Raw Ore Zhu Ni · Classic Form · Calligraphy Engraving)

「大刻壶 · Grand Script」 — 540ml Handmade Yixing Purple Clay Teapot (Raw Ore Purple Mud · Large Capacity · Calligraphy Engraving)